What’s the difference between voltage and current? #

Voltage and current are the two ways we measure electricity, like we use pressure and flow rate to describe water flow in a pipe.

Current #

Current is easier, so let’s start with that. Current is a measure of how many electrons are flowing past a point per second. Current is measured in amperes, called amps for short, and abbreviated “A”. 1 amp means that 6.24 x 1018 electrons per second are flowing. That’s 6.24 quintillion electrons. Physicists call that number of electrons a coulomb. A chemist might call it around 100 micromoles. A baker might call it 500 quadrillion dozens of electrons. It’s a lot of electrons.

To give you an idea of scale, microcontrollers and phones run on currents of 1-100 mA (“mA” is a milliamp). A blender or a vacuum cleaner might pull 1-15 A. (Wall outlets are rated for 15 A before a circuit breaker trips, usually.) Electric cars draw 100-1000 A.

Voltage #

But current doesn’t tell the whole story. Voltage tells the rest.

Current tells us about the rate at which electrons are flowing, and you would guess that those electrons have some potential to transfer energy, but the value of the current doesn’t tell us how MUCH energy the electrons are transferring each second. To know that, we have to know how much voltage is applied. Voltage, also called “potential difference,” tells you where energy is transferred in a circuit. If there’s a difference in voltage across something, then that thing is transferring electrical energy to some other form. Voltage is a measure of potential energy per electron.

Voltage has an “energy” definition and a “practical” definition. The energy definition is that 1 volt equals 1 joule per coulomb. In other words, voltage is the energy supplied per unit of charge.

\[1 V = 1 J / 1 C\]If 1 volt is applied, 1 joule of energy will be supplied by each coulomb that flows in a circuit. That’s like giving each coulomb of electrons enough energy to lift 1 newton up a distance of 1 meter in 1 second, if the system could convert the energy with perfect efficiency.

The practical definition of 1 volt is 1 watt per 1 amp. It’s the power consumed per unit of current drawn by a device. If 1 volt is applied, 1 watt of power will be consumed for each 1 amp of current.

\[V = W / A\]and

\[watts [W] = volts[V] * amps[A]\]A lot of us have the equation for Ohm’s law, \(V = IR\) , committed to memory. But Ohm’s law should not be viewed as a definition of voltage. Instead, it defines resistance, as the ratio of the voltage applied to the resultant current flow.

Circuits as energy conversion devices #

This video situates the concepts of voltage, current, resistance, and power in a view of circuits as energy conversion devices.

Two useful circuit analogies #

Every circuit analogy is flawed in some way, but the “cliff and rockslide” and “pump and water wheel” models can be quite useful for making basic sense of what will happen to a circuit when you change a voltage source or add a load.

Kirchhoff’s Current Law #

There are two rules that can be useful in thinking about electricity flowing in circuits. When mathematicians and similar notation enthusiasts describe Kirchhoff’s current law, they do it like this: \[\sum_{k=1}^{n} I_k = 0\] The letter \(I\) refers to current, because, according to Wikipedia, it was long ago an abbreviation for intensité du courant. So the idea is that if you add up all the currents going in or out of any point in an electrical circuit, the currents will always add up to zero. But that’s a weird way of saying something that you all already understand in a different context, which is that all the water that goes into a network of pipes also comes out of that network of pipes.

For example, take a pipe with 7 liters/minute flowing into it, which splits into two pipes. One of the pipes has 4 liters/minute coming out of it.

How fast is water coming out of the other pipe?

Now let’s try the same thing with electricity. We have a circuit where 7 mA are flowing into a junction. 4 mA are coming out one wire.

How much current is coming out of the other wire?

Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law #

Unfortunately, there is another law that is also typically taught in an obfuscated way: Kirchhoff’s voltage law, which is that the sum of the voltages around any loop is zero.

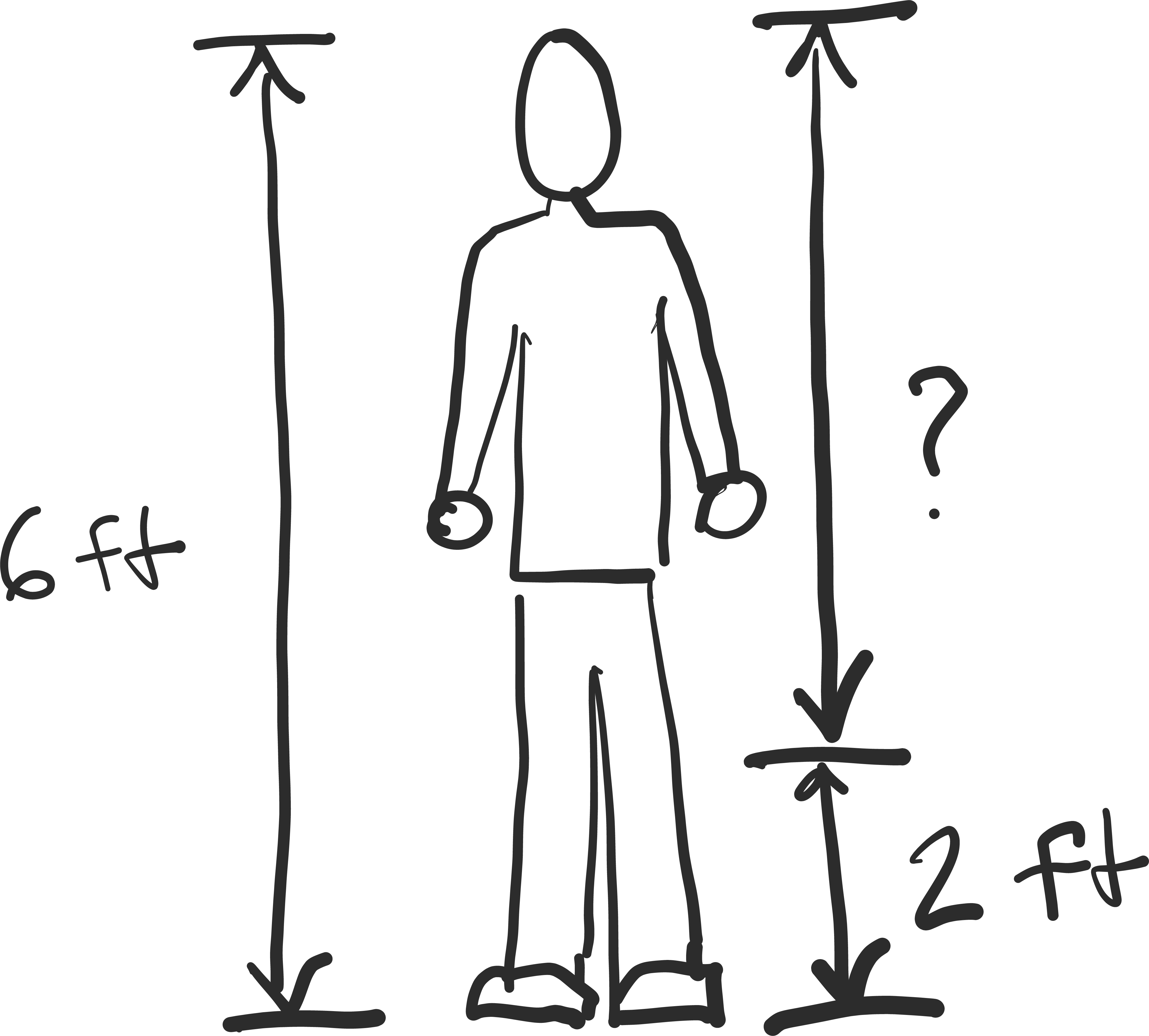

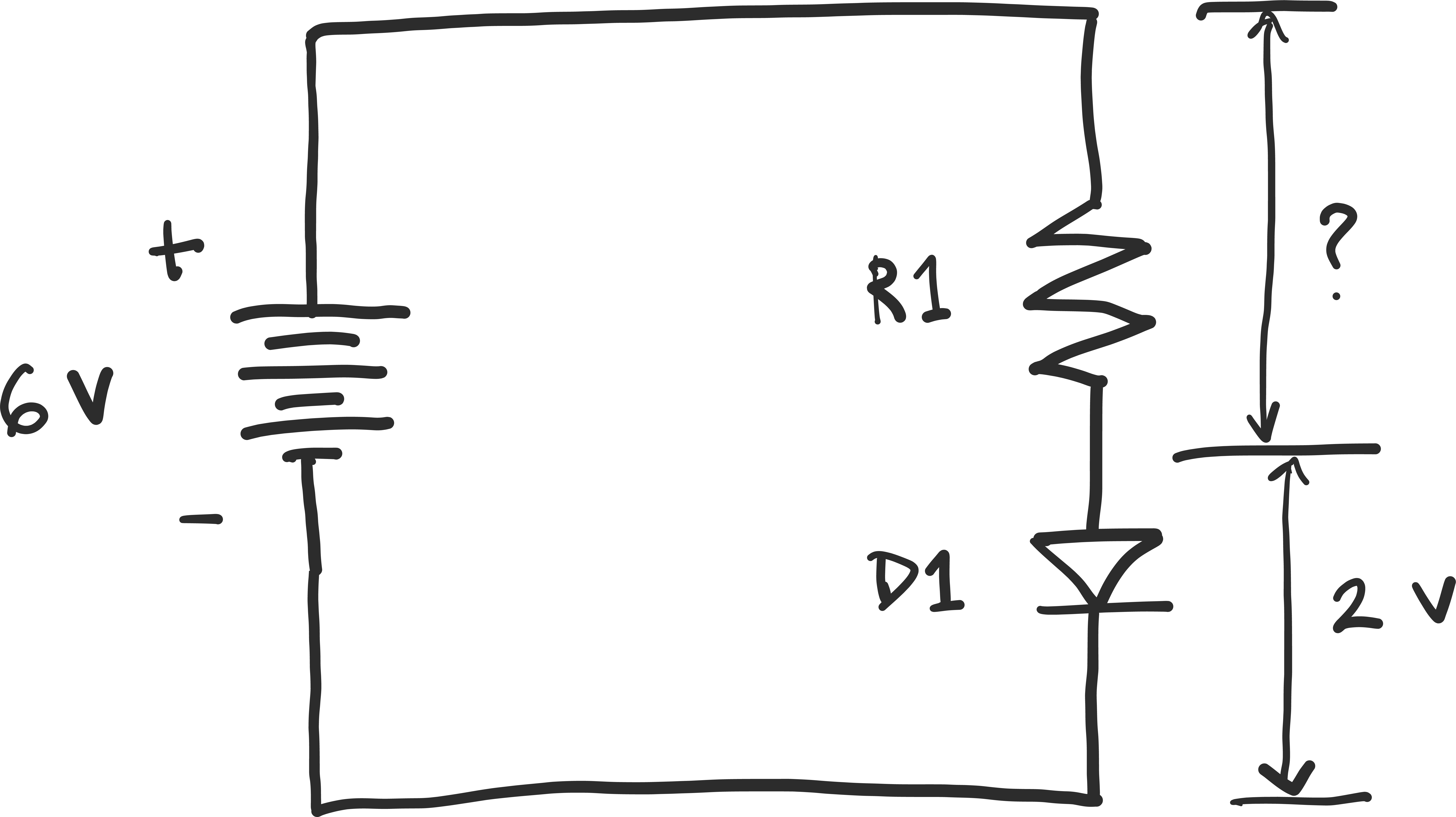

\[\sum_{k=1}^{n} V_k = 0\]But you know how to use a tape measure, right?

If I am 6 feet tall, and it’s 2 feet from the bottom of my feet to my knees, how far is it from my knees to the top of my head?

Voltage works the same way.

If you have a circuit run by a 6 V battery, and there is a 2 V drop across the LED, how many volts are there across the resistor?